(Cover image credit: Calm the Farm)

On this website, I have written how the hydroxyl radical, derived from water vapour in the presence of ultraviolet light (UV), oxidises methane. This is simplified but essentially correct, but I went on to claim that the quantum of hydroxyl radicals produced in a pastoral setting is sufficient to oxidise all of the methane produced by ruminants.

I can no longer confidently make that claim. Atmospheric dynamics are very complex, but it seems that most hydroxyl radicals are produced in the tropical zone, suggesting that the contribution from Aotearoa is relatively small.

However, I am disinclined to remove the relevant pages from this website for the following reasons.

The science is not settled

While I trust that CO2 can be quantified reliably in parts per million, the hydroxyl radical (OH) is ephemeral and hard to measure. Its typical lifetime is about one second, so collecting it for analysis is nigh impossible. It is present in minute traces compared to more common atmospheric substances.

OH is hard to measure, so we rely on models to estimate global methane lifetimes. But because “all models are wrong but some are useful,[1]” The challenge is to ensure that our methane and OH models are helpful in guiding policy, and not misleading due to oversimplification, poor validation, or political misuse.

Does methane modelling consider sources and sinks? In addition to the hydroxyl radicals produced in the atmosphere, methanotrophic bacteria also oxidise methane in well-drained aerobic soils. Soil sinks accounted for 6.2% of global sinks in 2020. While methanotrophic soils are important globally, their capacity is limited: one hectare of pasture typically oxidises only a few kilograms of methane per year, while a single dairy cow emits over 100 kg. Soil sinks matter globally but cannot, on their own, offset ruminant emissions.

New science is often challenging and modifying existing conceptions. A case in point, a 2024 paper claimed that rates of carbon sequestration by plants have been underestimated.

Nature-based solutions are underappreciated

The contribution of nature-based solutions is underappreciated. The nexus of science and policy focuses mainly on atmospheric dynamics of greenhouse gasses (GHGs) as they are relatively easy to model (the Keeling Curve).

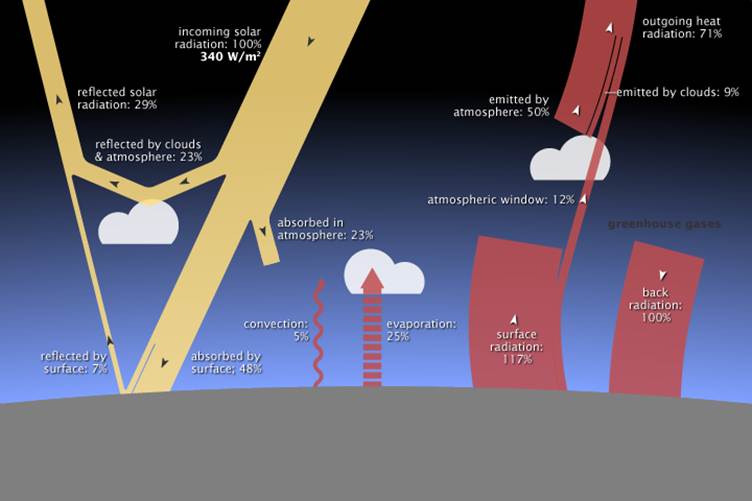

There is more to global warming than the insulating impact of GHGs. A brief study of the NASA energy budget reveals 340 watts/m2 of incoming solar radiation at the top of the atmosphere, with 29% of that reradiated. Notice that surface radiation of sensible heat is 117% of the incoming radiation. In the NASA chart, the percentages are flux components rather than fractions of a whole – they represent continuous energy flows within the Earth system. What matters for climate is that land-cover change alters these fluxes dramatically, especially via evapotranspiration and surface roughness. Our activities on Earth contribute to global warming. The removal of half of the world’s vegetation has a lot to do with warming, including:

- loss of latent heat flux

- loss of evapotranspirational cooling

- lower albedo/changed albedo

- reduced cloud formation

- soil moisture decline

- carbon loss from soils and biomass.

Its not a contest between reducing GHGs, or nature-based solutions, both are required to heal the climate.

Earth’s energy budget. Image credit NASA

When animal farming is done well, it contributes to healing the climate. Diverse pastures with a diverse rhizosphere interacting with the soil biome can sequester a lot of carbon, yet there are few examples of soil carbon budgets in Aotearoa, as it is hard to model and ground-truth. Grazing pasture is the farming equivalent of the permaculture chop and drop, with the addition of the soil-building benefits derived from the pasture being processed by a ruminant. Actively growing pasture also transpires, thus cooling the atmosphere in contrast to the known and ground-truthed phenomena of urban heat islands. These benefits occur in well-managed, diverse, non-overstocked pasture systems. They are not universal across all ruminant production models.

The multiple benefits of regenerative practices are explored in this website.

Anti-animal agriculture rhetoric

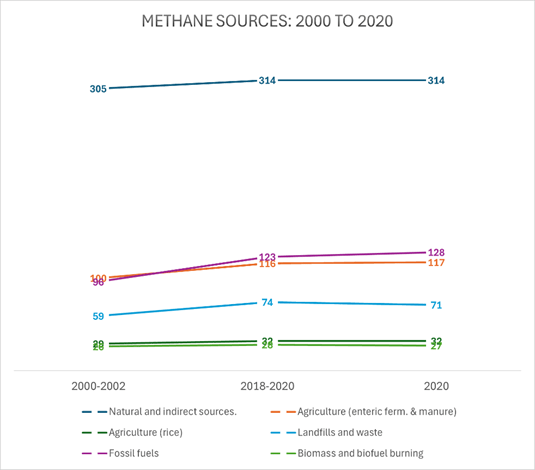

The adoption of regenerative agriculture is an encouraging trend in efforts to heal the climate. However, ruminants are singled out for vitriol, especially in Aotearoa. These graphs from Human activities now fuel two-thirds of global methane emissions (page 3) show the relative sources of methane. Both graphs use bottom-up (BU) rather than top-down (TD) data, as it is more complete. The numbers represent teragrams per year. The first graph shows the relative amounts of methane sources. The large teal segment is natural sources, not differentiated here. Rice cultivation produces about a quarter as much methane as enteric fermentation and animal manure.

This graph shows the trends over the three reported periods.

Note that fossil emissions are increasing faster than agricultural emissions from ruminants (enteric fermentation and manure). Not included here are artic and marine methane. There is significant uncertainty around potential methane feedbacks from Arctic permafrost and marine hydrates. While some studies warn of substantial future releases, others find more modest risk. Either way, these sources lie outside human control, strengthening the case for reducing controllable emissions.

So if you eat rice, or take organic waste (wood, natural fabrics, vegetation) to landfill, or use natural gas or products made for natural gas, please eliminate those uses before dumping on animal agriculture.

We also need a more nuanced critique of animal agriculture. Surely ruminants raised in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) or in this country’s intensive dairy farming generate more methane than ruminants raised on diverse pastures in environments that create more sinks. Diet composition, feed quality, stocking rate, and manure handling all influence methane intensity. Evidence suggests that well-managed, diverse pastures can lower methane per unit of production and increase local sinks, but this varies and requires further research.

This is the first of a series of posts on this topic. Future posts will explore:

- More on methane, science and agriculture

- Worldviews

- The three legs of the climate action stool

- Building community

The purpose of this series is not to exonerate any sector but to encourage a deeper, science-based, systems understanding of methane, land use, and climate healing. Oversimplified narratives help nobody. What we need is nuance, humility, and evidence-guided action that restores the living systems upon which climate stability depends.

Note: The Climate Change Tai Tokerau Northland Trust has trustees with diverse perspectives. We welcome that diversity. These are my thoughts and don’t necessarily represent the collective thinking of the trustees. The comments section is open and you are free to express your thinking in a spirit of moderation and mutual respect.

[1] George Box, in Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces by Box & Draper, 1987